Another Article About the Neck . . . or Is It?

While the neck is a bridge, a pathway, the position of the neck and head can also indicate a multitude of other things happening beneath the surface.

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) is one of the most common disorders affecting women post pregnancy. In fact, almost one in four women in the US suffer from one or more pelvic floor disorders, such as urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse (uterine, intestinal, or bladder), fecal incontinence, or vaginal vault prolapse caused by musculofascial and/or neurological changes in the pelvic floor as the result of trauma and age.1 A study by the National Institutes of Health found that 40 percent of women between the ages of 60 and 79, and 50 percent of women over the age of 80, suffer from PFD.2 And that number is only expected to increase, with estimates of 43.8 million PFD cases by 2050, up from 28.1 million cases in 2010.3

Understanding the physiology of PFD, and the options for treatment, is important when treating aging clients. Clients who are on our tables—or will be—tend to feel shame at the effects of PFD, and may not want to talk about the subject—unless you're willing to introduce it. Use the following statistics to inform clients who may be suffering in silence.

Affecting both women and men, PFD can be attributed to five key pathologies: age, obesity, chronic pathological conditions that cause an increase in abdominal pressure, past surgical interventions in the pelvic area, and, for women, injuries while giving birth.4 According to researchers,5 the most prevalent cause of PFD by far, among women, is giving birth.

When I was pregnant with my first child, I did my research on the safest options, created a birth plan, spoke endlessly with my doctor about the likelihood and risks of various outcomes, and considered myself fairly well educated on the entire process. I knew that C-sections were on the rise in the late 1990s and that there were a lot of complications that could arise from major surgery. I also knew that interventions such as inductions and epidurals were being cited as catalysts that could lead to emergency C-sections. Because of this information, I decided I wanted to deliver vaginally, without any interventions if possible—a natural birth. When the time came, I was able to deliver naturally and required only a couple of stitches in a hospital that was known for interventions and cesareans; I felt highly empowered by the process.

The following day, all the new mothers in the ward were given a short "how to" lesson on caring for newborns and were sent home with advice to avoid strenuous physical activity, like vacuuming and heavy lifting, and a reminder to "do your Kegels." Not one person told me to avoid going up and down stairs due to the stitches, nor to stay home and rest for the first month due to the trauma that my pelvic floor and uterus had just undergone. I told myself I was a strong, independent, and perfectly capable woman who wasn't sick but had just performed the most natural of acts—something the female body is designed to do.

A couple years later, I delivered my second child (again a natural birth) at a birth center with three midwives. As before, I required a few stitches but suffered no other complications or issues. The midwives had me wait for an hour to ensure everything was OK, and then sent me home. Unlike the hospital, though, I was given instructions to rest and avoid going up and down stairs so that the perineal tissue would have a chance to heal properly.

I was also advised to avoid heavy lifting, but there was no mention of why it was necessary to rest and rebuild my core and pelvic floor. I knew nothing about postpartum massage, pelvic bone alignment, abdominal support girdles, or Mayan abdominal massage, and certainly nothing about internal pelvic floor fascial massage to release fascial adhesions that form during pregnancy and delivery. And so, my journey began.

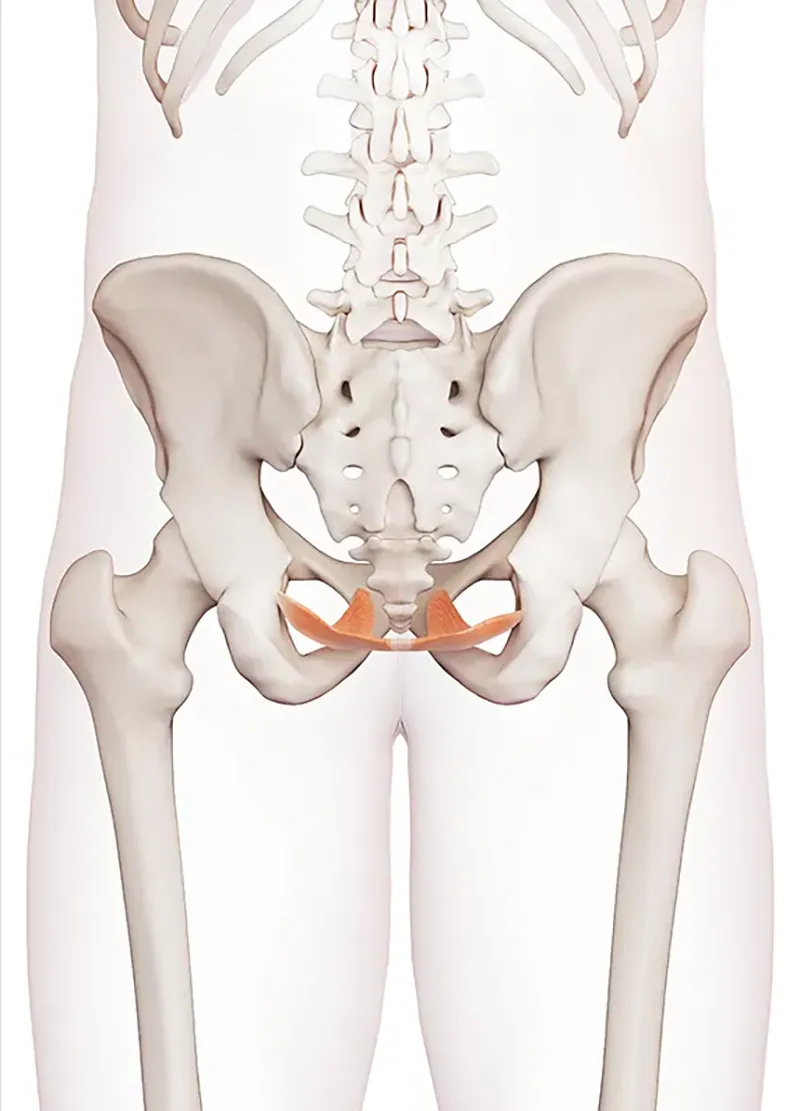

The pelvic floor is made up of muscles, connective tissue, and ligaments that lie within the opening of the pelvis to form a diaphragmic sling. In women, it is responsible for three major actions: supporting and keeping our abdominal and pelvic organs (such as the bladder, uterus, bowel, and intestines) in place; acting as resistance against increased intra-abdominal pressure; and opening and closing of the levator hiatus, which is responsible for contracting the sphincter for the urethra, vagina, and anus.6 This sling is also referred to as the second diaphragm because it not only supports our lower organs, but it moves caudally as the respiratory diaphragm contracts, allowing more room for lung expansion during inhalation and returning to its original resting place upon exhalation.7

During pregnancy, as the baby grows and expands, pushing internal organs aside and stretching fascia to make room, the extra weight puts a lot of pressure on the perineal structure to support the pelvic floor muscles, as well as the blood vessels and nerves that supply the urinary tract.8 During a vaginal delivery, the passage of the baby through the vaginal canal exerts tremendous pressure on the perineum and supporting tissues. This pressure can cause lasting damage to pelvic muscles, overstretch connective tissue and ligaments (resulting in scarring and adhesions causing future muscular imbalance), and cut off blood supply to the nerves that make up the pelvic floor.9 Experts say that "compression and stretching of the pudendal nerve during childbirth appears to be a major risk factor associated with subsequent diminished levator muscle function . . . and for some it is likely to be the first step along a path leading to prolapse and/or stress incontinence."10 Research is proving this out.

These devices help support the weight of the baby, relieving pressure on the pregnant woman's pelvic floor muscles, which are responsible for supporting the uterus. They can also assist in the stabilization of the mother's sacroiliac joint.

Developed by Rosita Arvigo, DN, this technique helps restore the new mother's body to its natural balance by correcting the position of organs that have shifted and opening up restrictions, including chi energy.

A specialized fascial massage technique, administered by highly trained practitioners, meant to help restore the muscles of the pelvis, reduce trigger-point pain, and bring balance to the pelvic bowl.

Specialized bodywork techniques that rebalance structure, physiology, and emotions of the new mother and help her to bond with and care for her infant.

Few doctors have the training to detect injuries like these and, after six months, the injury usually becomes impossible to detect. As a result, a majority of women who experience such injuries during childbirth discover them only years later when they suffer from incontinence or prolapse. Generally, at the six-week postpartum checkup, the gynecologist is looking to make sure the uterus is returning to its normal size and any tears to the perineum are healing well and free of infection; anything outside of that, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, is not considered a priority unless the new mother brings up concerns. Unfortunately, many times patients are told that symptoms related to pelvic floor disorders are normal after childbirth, leaving women to quietly struggle with these issues on their own. And yet, "It takes less than 30 seconds for a physician to evaluate muscle tissue and pelvic injuries during the internal exam," says Stephanie Prendergast, a physical therapist and founder of the Los Angeles-based Pelvic Health and Rehabilitation Center.15

We know that fascia surrounds every structure in the body, including organs, blood vessels, bones, nerve fibers, and muscles, literally holding them in place and providing both "form and function to every tissue and organ. Think of fascia as being like a nylon that surrounds and holds each muscle fiber, organ, nerve fiber, bone, and blood vessel in its place while maintaining its own nervous system, thereby making it almost as sensitive as skin that can tighten up when stressed."16 When we get injured, tense, or sit with bad posture over long periods, our fascia can snag, twist, and adhere to itself, which results in a constriction of blood, lymph, and nerves, and creates an imbalance in muscle contractions. If we perform Kegels (repetitive contraction and release of the pelvic floor muscles)17 with fascial imbalance, we only exacerbate the condition by strengthening the stronger areas while the portion of pelvic floor that has undergone trauma, such as scarring or adhesions (also referred to as tender or trigger points), will continue to remain weak.

When a trigger point is formed, it is not always an indicator of muscle damage. Fascial adhesions can form a blockage causing a "disruption of the cell membrane, damage to the sarcoplasmic reticulum with a subsequent release of high amounts of calcium-ions, and disruption of cytoskeletal proteins, such as desmin, titin, and dystrophin."18 When a trigger point forms and causes a clinical complaint, it is referred to as an active trigger point, which always feels tender to the touch and painful upon compression and/or causes radiation of pain toward a zone of reference. The effects of an active trigger point are muscle weakening, prevention of full lengthening of the muscle, and localized spasm response when muscle fibers are sufficiently stimulated.19 A latent trigger point may share all the clinical characteristics of an active trigger point, but its presence is not always recognized because it does not cause spontaneous pain (defined as pain at rest),20 but only registers as pain when compression is applied directly to the tender point. A latent trigger point always has a taut band that increases muscle tension and restricts range of motion. Another key factor is local ischemia, which leads to a lowered pH and a subsequent release of several inflammatory mediators in muscle tissue.21

Twenty years after the birth of my first child, I joined the ranks of women with PFD and developed a cystocele (herniated bladder). As a classically trained dancer, exercise and fitness have always been a part of my life. Pregnancy and childbirth-related changes in my body left me with a weak core that resulted in pelvic instability and back pain. I turned to Pilates to build my core, and the large positive changes I experienced in my body subsequently compelled me to pursue certification as a Pilates instructor. Although I am convinced that my cystocele condition might have been far worse had I not worked on strengthening my core through Pilates, the fact remains that in my case it was insufficient.

Soon after becoming an LMT, I began to study the pelvic muscular structure and research alternative therapies, such as internal pelvic massage, that might help with my PFD. Just two sessions of internal fascial release, by a specialist certified in Holistic Pelvic Care, improved my pelvic balance to the point where I could begin to strengthen my pelvic floor with regular Kegels. A follow-up appointment with a urogynecologist, two months later, confirmed that my cystocele had improved. My doctor mentioned her experience has led her to routinely prescribe a combination of core strengthening through Pilates and pelvic physical therapy to her PFD patients. Having been recently certified in prenatal/postnatal massage, and being within my scope as an LMT practicing in Oregon (which, with proof of specialized training, allows for internal cavity massage), I subsequently enrolled in pelvic floor massage training so I could serve my postpartum clients in a more holistic way. My personal experience and research have led me to believe that pelvic floor massage, coupled with postpartum massage, are essential preventive measures to reduce childbirth-related PFD in women.

The feelings of shame that often accompany the effects of PFD can cause women to suffer in isolation for many years before seeking medical assistance. Depending on the severity of the pelvic dysfunction, doctors may recommend a range of remedies for pelvic care, including, in severe cases, surgical intervention. In the US, pelvic care is generally not prescribed until a woman develops clear symptoms of PFD and seeks medical advice.

In stark contrast to the American system of postpartum care, French women are encouraged to meet with a physiotherapist or midwife twice a week for six weeks after childbirth to reduce muscular tensions and scar tissue. The women are then prescribed a minimum of 10 supervised sessions of core exercises and abdominal muscle rehabilitation to counter diastasis and rebuild core strength.22

Many times patients are told that symptoms related to pelvic floor disorders are normal after childbirth, leaving women to quietly struggle with these issues on their own.

Research clearly suggests that the process of vaginal childbirth exacts a significant toll on pelvic tissue, greatly increasing the probability of PFD as women age.23 Since we know that so much of PFD is related to muscular and fascial trauma, it seems likely that early and preventive pelvic massage after childbirth may help reduce the number and/or degree of pelvic dysfunctions in women, allowing them to live fuller lives without the pain and embarrassment of PFD. I believe that by working with a pelvic floor therapist as a first-line, minimally invasive therapy for preventing and treating PFD, fascia can be relaxed, allowing blood and lymphatic fluids to flow freely to our muscles, joints, bones, organs, and nervous system, allowing all to work more effectively.24 Such work, over both the short and long term, can increase range of movement in the muscles and fascia, resulting in an increased ability to either contract or release muscles evenly, thus improving muscle function that would allow for proper pelvic organ positioning.25

1. Ylenia Fonti et al., "Post Partum Pelvic Floor Changes," Journal of Prenatal Medicine 3, no. 4 (October-December 2009): 57-59, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3279110.

2. National Institutes of Health, "Roughly One Quarter of U.S. Women Affected by Pelvic Floor Disorders: Weakened Pelvic Muscles May Result In Incontinence, Discomfort, Activity Limitation," September 17, 2008, www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/roughly-one-quarter-us-women-affected-pelvic-floor-disorders.

3. Hafsa Memon and Victoria Handa, "Vaginal Childbirth and Pelvic Floor Disorders," Women's Health 9 (May 1, 2013): 265-77, https://doi.org/10.2217/WHE.13.17.

4. Kegel8, "Prolapse after Childbirth," accessed November 2020, www.kegel8.co.uk/advice/prolapse/causes-symptoms-prolapse/prolapse-after-childbirth.html.

5. Jennifer L. Hallock and Victoria L. Handa, "The Epidemiology of Pelvic Floor Disorders and Childbirth: An Update," Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 43, no. 1 (March 2016): 1-13, https://doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2015.10.008.

6. Varuna Raizada and Ravinder K. Mittal, "Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Applied Physiology," Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 37, no. 3 (September 2008): 493-509, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2617789.

7. Bruno Bordoni, Kavin Sugumar, and Stephen W. Leslie, "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pelvic Floor," StatPearls, updated August 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482200.

8. Sophie Fidoe, "The Perineum," TeachMe Anatomy, updated November 12, 2019, https://teachmeanatomy.info/pelvis/areas/perineum.

9. Kegel8, "Prolapse After Childbirth."

10. R. E. Allen, G. L. Hosker, A. R. Smith, and D. W. Warrell, "Pelvic Floor Damage and Childbirth: A Neurophysiological Study," British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 97, no. 9 (September 1990 ): 770-79, https://doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02570.x.

11. Ingred Nygaard et al., "Prevalence of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in US Women," Journal of the American Medical Association 300, no. 11 (September 17, 2008): 1311-16, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

12. Victoria Handa, Alvaro Muñoz, Megan Carroll, and Joan Blomquist, "Delivery Method Associated with Pelvic Floor Disorders after Childbirth," John Hopkins Medicine Newsroom, December 19, 2018, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/delivery-method-associated-with-pelvic-floor-disorders-after-childbirth.

13. T.J. Mathews and Brady E. Hamilton, "Mean Age of Mothers Is on the Rise: United States, 2000-2014," NCHS Data Brief 232 (January 2016): 1-8, www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db232.pdf.

14. J.A. Ashton-Miller and J.O. Delancey, "On the Biomechanics of Vaginal Birth and Common Sequelae," Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 11 (2009): 163-176, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124823, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2897058.

15. Kiera Butler, "The Scary Truth about Childbirth: Having a Baby Left You with a Horrible, Debilitating, Embarrassing Injury? You're Not Alone," Mother Jones Magazine, January/February 2017, www.motherjones.com/politics/2017/01/childbirth-injuries-prolapse-cesarean-section-natural-childbirth.

16. John Hopkins Medicine "Muscle Pain: It May Actually Be Your Fascia," John Hopkins Medicine Newsroom, accessed November 23, 2020, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/muscle-pain-it-may-actually-be-your-fascia.

17. "Kegel Exercises," Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, accessed November 23, 2020, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kegel%20exercises.

18. Carel Bron and Jan D. Dommerholt, "Etiology of Myofascial Trigger Points," Current Pain and Headache Reports 16 (October 2012): 439-44, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-012-0289-4; B. Larsson et al., "The Prevalences of Cytochrome C Oxidase Negative and Super Positive Fibres and Ragged-Red Fibres in the Trapezius Muscle of Female Cleaners With and Without Myalgia and of Female Healthy Controls," Pain 84, no. 2-3 (February 2000): 379-87, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00237-7.

19. Carel Bron and Jan D. Dommerholt, "Etiology of Myofascial Trigger Points."

20. Sanna Malinen et al., "Aberrant Temporal and Spatial Brain Activity During Rest in Patients with Chronic Pain," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, no. 14 (April 6 2010): 6493-97, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001504107.

21. Janet G. Travell and David G. Simons, Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1993).

22. Claire Gagne, "Why French Women Don't Pee Their Pants When They Laugh," Chatelaine Magazine, updated March 20, 2019, www.chatelaine.com/health/lady-bits/pelvic-floor-physiotherapy; Marcy Crouch, "The French Know What's Up Down There," Healthline Parenthood, reviewed on May 28, 2020, accessed November 2020, www.healthline.com/health/parenting/the-french-know-whats-up-down-there.

23. Ilknur Kepenekci et al., "Prevalence of Pelvic Floor Disorders in the Female Population and the Impact of Age, Mode of Delivery, and Parity," Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 54, no. 1 (January 2011): 85-94, https://doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fd2356.

24. Shannon L. Wallace, Lucia D. Miller, and Kavita Mishra, "Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy in the Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in Women," Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 31, no. 6 (December 2019): 485-93, https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000584.

25. R. U. Steinberg, "You Want to Do What? Where? Internal Pelvic Floor Therapy Gives New Meaning to Inner Journeys," The Austin Chronicle, November 18, 2010, www.austinchronicle.com/daily/chronolog/2010-11-18/you-want-to-do-what-where.

While the neck is a bridge, a pathway, the position of the neck and head can also indicate a multitude of other things happening beneath the surface.

Understanding fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix changes how we think about the tissue we touch.

Studies reveal that 37 percent of the force generated by muscle contraction is transmitted to adjacent connective tissue structures instead of the bones.

Ongoing research suggests the sciatic nerve's healthy functioning depends on its fascial connections.